** spoiler alert **

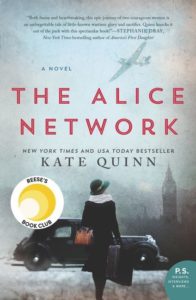

The Alice Network by Kate Quinn is a raw, vivid, moving account of two women’s stories: Evelyn Gardiner, a spy in World War I and nicknamed Eve, and Charlotte “Charlie” St. Clair, an American searching for her French cousin lost in World War II. Eve and Charlie at first seem foils for each other. As their stories unfold, overlap, and intertwine, they seem more like mother and daughter, tethered by a shared grief and quest for justice.

This is the first book of Quinn’s I’ve read. She employs a unique brilliance as she sends readers on a believable exploration of good and evil in both World Wars. Her depiction of post-war France is well-done, her character development of Charlie and Eve shows marked transformation. Quinn keeps readers turning pages with her deft use of strong verbs and colorful prose. She evokes tears, disgust, and joy.

This is the first book of Quinn’s I’ve read. She employs a unique brilliance as she sends readers on a believable exploration of good and evil in both World Wars. Her depiction of post-war France is well-done, her character development of Charlie and Eve shows marked transformation. Quinn keeps readers turning pages with her deft use of strong verbs and colorful prose. She evokes tears, disgust, and joy.

After reading the book, I have a new appreciation for the achievements of female spies. What sacrifices they made to save lives and help rout the Germans. Yet my readerly contempt was focused on the French turncoat, René. Quinn masterfully constructs him as someone to be loathed. War turns everyone inside-out—winners, losers, and those in-between. No one really wins, though. Some manage to survive. Survivors are haunted by unfading images of mankind at its worst.

Women have long been oppressed. Evidence of that was stark during the world wars. Female spies sharpened the dull ends of their oppression into weapons of knowledge, turning it on their unwitting enemies. When women work together—not against each other, as we often do—we achieve remarkable feats. We help win wars. That’s the stuff of this book.

At the book’s end, I would’ve preferred to see René hauled off to trial and sentenced to life in prison. I understand that his death helped bring closure for Eve, but like Charlie had said, it let him off too easily.

On Goodreads, I gave the book four stars. I refrained from giving it five because of its overemphasis on intimacy and bedroom scenes, especially with Charlie. I see the importance of it with Eve and René. But less is more. Quinn could’ve suggested intimate scenes and allowed the theater of her readers’ minds to do the rest.

On the whole, this is an excellent read. I got through most of it in audio form. But my print copy is marked up with instances of well-crafted sentences and phrases, like “No fatal streak of romanticism or nobility in her [Eve’s] soul, not like Cameron’s [Eve’s boss in World War I].” Quinn used these words to explain why Cameron fell by his own hand.

I appreciate how Quinn depicts Cameron’s suicide and that of Charlie’s older brother, James, a WWII veteran. My brother ended his life six years ago. He wasn’t a former soldier with PTSD. He fought a personal war that spurred a PTSD-esque response as violent and wretched as those of James and Cameron. My brother shared their romantic streak of romanticism and nobility. That streak fueled his belief of how life should be. That streak was my brother’s wiring, his hamartia.

Tragic flaws lie within us all, pointing to our brokenness. But as Charlie aptly says, we don’t need to stay broken. When the book opens, Eve and Charlie languish in their brokenness. Throughout the book they serve each other as unlikely sources of redemption, giving way to healing and hope—for themselves, and their readers.

Leave a Reply