When the Allies stormed five beaches in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, 160,000 troops swung into action—along with one woman. Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent, was the only female to join their ranks. She was the first journalist to reach the beaches and report on what happened.

When the Allies stormed five beaches in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, 160,000 troops swung into action—along with one woman. Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent, was the only female to join their ranks. She was the first journalist to reach the beaches and report on what happened.

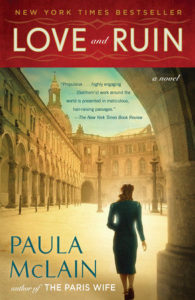

D-Day is the capstone of Love and Ruin, Paula McLain’s novel about Gellhorn’s early career and her relationship with Ernest Hemingway. D-Day marks the ruinous end of their marriage, and a pinnacle of her life as a combat reporter.

While covering the Spanish Civil war, Gellhorn finds her greatest loves: telling stories of ordinary people as they grind through extraordinary circumstances, and Hemingway. Readers are plunged into Gellhorn’s affair with Hemingway, who’s married. Their intimacy is tastefully suggested, and the rest is left to the theatre of the reader’s mind.

McLain is a master of showing and telling. Avoiding salacious details, she employs strong verbs and artful prose to send her characters on transformational arcs.

Gellhorn and Hemingway are at their best in Spain. They cling to each other while the world around them crumbles, becoming literary muses for each other. Later, they build a private paradise in Cuba, and Hemingway presses for a divorce from his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. Meanwhile, he writes For Whom the Bell Tolls, one of his most popular novels.

Opposing forces vie for Gellhorn’s heart and mind. More than anything, she relishes the freedom to travel to far-flung, often-dangerous places. She seems made for the razor’s edge. Amid ashes and doom, she does her best work. It’s against her own wisdom—and her mother’s—that she capitulates to Hemingway:

[H]e’s such a force of nature. He pulls everything into his orbit and seals off the corners and any route of escape. He does it all without trying, and with very little self-awareness.

Gellhorn’s inner voice pleads with her not to marry Hemingway. Three-quarters of the way through the book, she becomes his third wife. In marriage, their white-hot romance fizzles. They mount an emotional tug-of-war. Neither of them wins. When Collier’s asks her to cover World War II on the European front, she seizes it, leaving Hemingway behind in Cuba.

Transforming Character

Most of the book is told from Gellhorn’s first-person point of view. Several chapters in Hemingway’s third-person point of view strip the veneer from the literary giant we think know—shameless womanizer, brazen narcissist, liquored-up life-of-the-party—to reveal a man at war with his weaknesses, wounds, and flaws.

His battles with loneliness and depression are constant. His emotional wounds are rooted in his childhood and his World War I tour of duty. In this novel and in The Paris Wife, about Hemingway’s first marriage, McLain shows us Hemingway’s tragic flaw: he copes with emotional pain by hurting others, especially his wives. Instead of confronting the pain, he scrapes it into the deepest recesses of his heart, cementing it with anger and rejection.

At the outset, Hemingway loves and admires Gellhorn more than anyone. He marvels at her bravery and writes a character based on her. Like Hemingway, she makes things happen, in her writing life and their relationship. They often mirror each other. But when Gellhorn leaves to cover WWII, Hemingway shatters. He believes she chose her work over him.

She visits him on leave from reporting, and he snarls at her, piling on verbal abuse. Without her knowledge, he calls Collier’s, offering to cover the war. With only one reporting slot and the chance to run a byline from the most celebrated American novelist of the day, Collier’s picks Hemingway.

Still smarting from the betrayal, Gellhorn manages to hitch a return ride across the Atlantic. It’s not the first time Hemingway’s long shadow threatens her. Once the media had discovered their relationship, they compared her work to his, condemning it as a less-shiny spinoff. Time Magazine said she couldn’t be a writer because her face was “too beautiful.”

Hemingway’s fame and status threaten her, but she’s never overpowered. As she fights for equal footing, her character is transformed. At the novel’s start, we see a young woman unsure of herself and what she wants to achieve. By the end, she’s a determined, confident war correspondent. She loses the paradise she had with Hemingway, and finds herself.

Hemingway, on the other hand, loses a piece of himself when he shuns Gellhorn. He’s more likable at the start of the book than at the end. Some readers have said McLain’s writing reinforces him as a self-absorbed “jerk.” But she also exposes his humanity and conjures empathy for him. The careful reader wonders whether his inability to cope with pain was a driver of his suicide in 1961.

More Than a Footnote

America is a culture of celebrity. We swoon over people who top the charts and rake in millions. Anyone who falls outside the orbit of stardom tends to go unrecognized. That could be said of Martha Gellhorn. Before reading McLain’s novels, I couldn’t name any of his four wives.

Love and Ruin reveals Gellhorn to be as remarkable and talented as Hemingway. In some ways, she’s more remarkable. She successfully thwarted norms that governed how women were supposed to behave in their personal and professional lives. She broke molds and braved her own way, unsure of where it would lead, and doing it anyway.

Gellhorn once asked, “Why should I be a footnote to someone else’s life?” The press coverage in her day sought to render her life and work as worth little more than a glance. Who she was and what she accomplished is worth far more. She blazed a path for women journalists, inspiring us to find the stories that matter, wherever they may be—or what society’s norms say.

Above all, Love and Ruin propels readers on emotional journeys of their own. Each of McLain’s novels does this, in rich-and-haunting ways. All historical fiction should be this powerful.

Leave a Reply