Today is World Mental Health Day. Every October 10, the World Health Organization asks those working in the mental-health arena to talk about what we do, and discuss ways we can improve and expand mental-health care for everyone, everywhere.

This year, the WHO is focused on suicide prevention. It’s an important focus. U.S. suicide rates have climbed 33 percent since 1999, the highest age-adjusted rate since 1942. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention told Time Magazine that while there’s no single cause for the increase, “a period of increased stress and a lack of a sense of security may be contributing.” The numbers are growing among people of diverse ethnic backgrounds, both genders, and across age groups.

Suicide prevention is a cause close to my heart. I lost my brother, Jim, to suicide in 2013. He led a successful, rewarding life on almost every front. He was an unlikely candidate for suicide. But a brief battle with depression was fierce enough to engulf and swallow him.

Making sense of suicide is nearly impossible. Suicide is a masterful slayer, brandishing arrows of deceit. It leaves its victims—and those on the sidelines—confused. We can’t know by looking at someone whether they’re content and fulfilled, or twisted in a relentless spiral of depression. To write suicide off as a cowardly act, or as a weakness, is to be misinformed. Sally Brampton offers words that point us in the right direction:

“Killing oneself is, anyway, a misnomer. We don’t kill ourselves. We are simply defeated by the long, hard struggle to stay alive. When somebody dies after a long illness, people are apt to say, with a note of approval, ‘He fought so hard.’ And they are inclined to think, about a suicide, that no fight was involved, that somebody simply gave up. This is quite wrong.”

I’m not an expert on suicide. I’ve written about it as a layperson, in an effort to bring hope and healing to others. You can read my reflections here.

I know more about another side of mental health: perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) often referred to as postpartum depression (PPD). After the birth of my first child in 2009, I experienced postpartum depression. A big part of my illness had stemmed from birth-related trauma and an autoimmune disorder I didn’t know I had.

When I was going through postpartum depression, I couldn’t find a book that offered true, detailed stories from other mothers who’d been where I was. There was plenty of clinical advice, but nothing from peers. What helped me most was the solace I received from other mothers, so I set out to capture that solace in print, and offer it to women for generations to come.

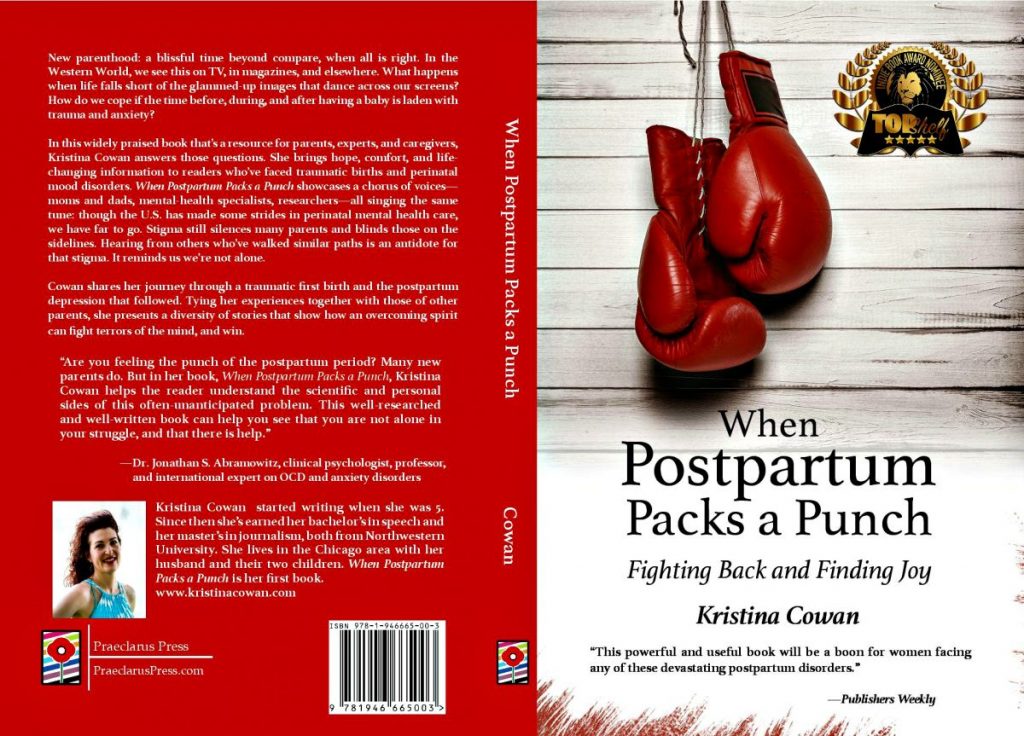

By the time I was pregnant with my second child, I was writing the book I couldn’t find. When Postpartum Packs a Punch: Fighting Back and Finding Joy, published in 2017. You can read Publishers Weekly‘s review of it here. It’s sold online, wherever books are—including Amazon—and it’s available at libraries in most states.

We need to protect and preserve our mental health, just as we do our bodies. Despite a growing awareness of this, stigma persists. As if mental illness isn’t debilitating enough, those struggling are often ravaged by shame, too.

In the spirit of changing this, and shedding light on an often-overlooked topic, below is an excerpt from my book. This is from chapter two, on traumatic births and post-traumatic stress.

What are Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders?

Postpartum depression often is used as an umbrella term for the different anxiety and mood disorders associated with child- birth. Though it’s just one of the disorders, many people have at least heard of it. Still, they might not understand the specifics, especially if they haven’t experienced it, or know someone who has. Mainstream media tends to focus on extreme cases, such as

Andrea Yates (Belluck, 2014), where a mother harms her child/ children, or herself. TV news coverage, for instance, highlights the horror of it all, and eclipses important details worth knowing. For instance, Yates suffered from postpartum psychosis—not postpartum depression. Psychosis is relatively rare, and many who experience it don’t harm their children or themselves: they get treatment, they recover, and they go on to lead productive lives.

Unless we make these distinctions between psychosis and postpartum depression, and educate others about all perinatal mood disorders, the public will continue to draw incorrect conclusions from well-publicized cases. It’s as easy as it is unfair to transfer those assessments to other women. Walling them in with our own suspicions and fears, we treat them as if they’re a threat to their children, themselves, or both. By doing so, we give stigma an undeserved license to continue silencing women. Afraid of being branded as crazy, unfit mothers, they don’t speak up and get the help they need. They often get worse, and their families languish as a result.

It’s a senseless spiral: sensationalized cases breed misinformation, which drives stigma that holds women captive, and bars them from getting medical attention. To break this pattern, we must first pull apart the sometimes-confusing terminology of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs), and offer clear, simple definitions.

PMADs can surface during pregnancy, or up to a year after childbirth. During pregnancy they’re called prenatal, antenatal, or antepartum. After a baby is born, they’re dubbed postpartum or postnatal. Some mothers develop more than one, so it’s important to be aware of the various symptoms and risk factors, and how common they are. Below is a list of five major PMADs:

- Prenatal/postpartum depression (PPD) can involve feelings of anger, sadness, irritability, guilt, lack of interest in the baby, changes in eating and sleeping habits, trouble concentrating, hopelessness, and sometimes, thoughts of harming the baby or oneself.

- Prenatal/postpartum anxiety (PPA) may be characterized by extreme worries and fears, often about the baby’s health and safety. Some women have panic attacks, shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, a feeling of losing control, and numbness and tingling.

- Prenatal/postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) might include repetitive, upsetting, and unwanted thoughts or mental images, known as obsessions. A woman also may have compulsions, where she does certain things over and over to reduce the anxiety caused by the unwanted thoughts. She is extremely disturbed by the thoughts, and very unlikely to ever act on them.

- Postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is often caused by a traumatic or frightening childbirth, or past trauma, particularly sexual abuse. Symptoms can include flashbacks to the trauma, with feelings of anxiety, and the need to avoid things related to the event.

- Postpartum psychosis (PP) is a break with reality. Women might see and hear voices or images that others can’t, called hallucinations. They may believe things that aren’t true and distrust those around them. They can encounter periods of confusion and memory loss, and seem manic. Though it’s relatively rare, psychosis is a severe, dangerous condition that needs immediate attention (Postpartum Support International, n.d.).

I take a closer look at each of these in the chapters ahead, through real-life cases, research, and expert perspectives. From this point, I use “PMAD,” “perinatal mood and anxiety disorder,” and “perinatal mood disorder” as general terms to refer to the different illnesses.

Two other conditions I won’t explore in-depth are postpartum stress syndrome (PSS) and bipolar mood disorder.

About one in five women experience PSS, the most common postpartum emotional reaction, but it isn’t as severe as postpartum depression. It involves feelings of anxiety, self-doubt, and a strong desire to be a perfect mother. Some women with postpartum stress syndrome develop clinical depression, but others don’t (Kleiman & Raskin, 2013).

Postpartum-depression expert Karen R. Kleiman explains that PSS is synonymous with the term “adjustment disorder,” as defined by the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The DSM-5 says that adjustment disorders are characterized by “emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor.” The stressor could be one event, or more than one (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

“Women with PSS generally don’t need medication, and may or may not need or want therapy,” says Kleiman, founder of The Postpartum Stress Center in Pennsylvania, a treatment and professional training center for prenatal and postpartum depression and anxiety. In treating PSS patients, she makes sure they’re sleeping well, connecting with their partner, and maybe joining support groups for mothers. “We see a lot of women who don’t have clinical depression, but would have an adjustment disorder.”

Bipolar mood disorder involves two phases: lows and highs. The lows are called depression, and the highs are known as mania or hypomania. Many women are diagnosed for the first time with bipolar depression or mania while they’re pregnant, or postpartum. The disorder may appear as a severe depression, so women need evaluation and follow-up on past and current mood changes and cycles to determine if there’s a bipolar dynamic (Postpartum Support International, n.d.).

The rest of this chapter examines trauma and postpartum PTSD. I focus first on this topic because threads of trauma run through all mood disorders. A traumatic birth, for instance, might lead to a mood disorder, and the illness itself is a form of trauma. An increased knowledge of trauma enables us to acknowledge how common it is. Recognizing the commonality will, ideally, help us release our fears of admitting that at some point—even with the births of our beloved children—we endure trauma.

Dr. Bessel A. van der Kolk, an international expert on post-traumatic stress since the 1970s, offers a clear explanation of what it means to be traumatized:

In the long term, the largest problem of being trau- matized is that it’s hard to feel that anything that’s going on around you really matters. It is difficult to love and take care of people and get involved in pleasure and engagements because your brain has been re-organized to deal with danger. It is only partly an issue of consciousness. Much has to do with unconscious parts of the brain that keep interpreting the world as being dangerous and frightening and feeling helpless. You know you shouldn’t feel that way, but you do, and that makes you feel defective and ashamed (Bullard, 2014).

Leave a Reply