Messages of isolation, division, and discouragement have bombarded Americans since 2020. If we dwell on the bad news leading most stories, we might think we have little to nothing in common with our neighbors.

Kansas City Chiefs’ kicker Harrison Butker summarized it well in his commencement address at the Georgia Institute of Technology:

“Our culture is suffering. We all see it. It doesn’t matter which political persuasion you sit on, or whether you are a person of deep faith or not. Anyone with eyes can see that something is off. Studies have shown one of the many negative effects of the pandemic is that a lot of young adults feel a sense of loneliness, anxiety, and depression, despite technology that has connected us more than ever before.”

Division has driven wedges between family and friends, splintering relationships. On the heels of harsh, unnecessary lockdowns, U.S. suicide rates increased in 2021, following two consecutive years of declines. Among adults between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four, suicide was up five percent.

Without purpose and meaning, human beings descend into despair. It’s almost as if the quest for meaning is more fruitless than ever, especially among young adults in the West.

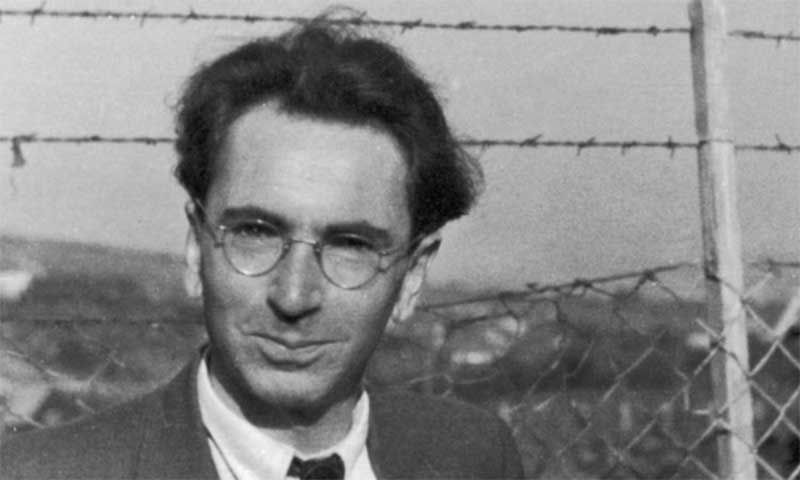

Holocaust survivor and psychotherapist Viktor Frankl grappled with the human pursuit of meaning, naming his bestselling book Man’s Search for Meaning. Mired by death, grief, and loss in the Nazi death camps, Frankl confronted the meaning of life. In his professional life, he developed a form of psychotherapy focused on meaning, called logotherapy.

Frankl explained that logotherapy “focuses on the meaning of human existence as well as on man’s search for such a meaning. According to logotherapy, this striving to find a meaning in one’s life is the primary motivational force in man.”

Man’s Search underscores that while we don’t control what life brings, we do control our response to even the most grim situations:

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

Until we encounter hardship, we often forget the importance of our responses.

Viktor Frankl’s legacy, logotherapy, helps patients find meaning in life. Photo by The Viktor E. Frankl Institute of America.

Our Common Quest for Logos

Logos is the Greek word for meaning or reason. Frankl dedicated much of his life to helping others find meaning. His legacy reminds us that we’re all in search of meaning. Whether it’s through our families, our work, our faith, or a combination of those, we all derive meaning from something. Without logos, life is meaningless.

My first brush with logos came about when my mom died. She had shared her faith in Christ wherever she went. It was her wellspring of meaning and purpose. At fifteen, I began exploring the Christian faith on my own—a journey that has continued for thirty-four years. In good times and bad, my faith has been my biggest source of meaning.

The older I get, the more meaning it holds. I’ve learned that the Christian faith hinges on a relationship with Christ. That seems untenable, given that He’s not materially accessible. The key lies in reading the Bible, both the Old and New Testaments. They beautifully reveal God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit: who they are, what they do, and what they ask of believers.

The Bible covers every aspect of the human condition, from despair to joy, rebellion to obedience, defeat to victory. Whatever we experience is mirrored somewhere in the Bible. It’s filled with wisdom and assurances.

This spring I delved into the Book of Isaiah, rich with meaning and imagery. For context, I’ve also been reading Ray C. Stedman’s Adventuring Through the Bible: A Comprehensive Guide to the Entire Bible. Stedman points to Isaiah 55:8-9, a reminder that God doesn’t operate like humans (thankfully):

“My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,” declares the Lord. “As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.”

Stedman goes on to illuminate this passage further:

God’s method is to break through human rebelliousness not by might, not by power, but by love, a costly love that suffers and endures great pain and shame. When God comes to the human race as a suffering Servant rather than as a mighty conqueror, something beautiful takes place: The human heart responds, opening to God as the petals of a flower open to the sun. And into that open heart, God pours His life, bringing to that human heart all the joy and fulfillment that He has always wanted His people to experience.

The Bible is a roadmap for life and ultimately, God’s love letter to humanity.

A Meaningful Legacy

Meaning lurks behind all of life’s twists and turns. It’s up to us to pursue it. That’s particularly true amid tragic losses or difficult seasons.

In my second book, When Losses Become Legacies: Memoirs on Grief, God, and Glory, I shared part of my own search for meaning in the face of significant losses. Last fall, I appeared on Patti Shene’s Blog Talk Radio show, Step Into the Light, to discuss Legacies.

I touched on the lifelong impact of losing a parent during childhood, the difference between complicated and uncomplicated grief, and offered advice for anyone grieving. Christy related her experience losing a close friend to breast cancer, and how her own health challenges have led to unique losses.

Legacies’ target audience is anyone who’s lost someone. Sooner or later, that’s all of us.

Leave a Reply