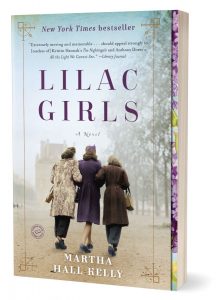

A friend of mine and I recently launched a book club. We’re a small band of readers bent on sharing our perspectives on excellent literature. Our first title is Lilac Girls, Martha Hall Kelly’s debut novel.

Bravo to Kelly for her extensive research. It lends credibility to all sides of the several stories in this sweeping novel set just before, during, and after World War II in America and Europe. The book focuses on the horror that was Ravensbrück, Hitler’s only all-women concentration camp near Furstenberg, Germany. It was a place planned for so-called deviant women, according to a 2015 piece in The Guardian.

Kelly’s creativity and knack for illuminating details are expertly on display. She does a masterful job of weaving fiction and history. Two of the central characters, Caroline Ferriday and Herta Oberheuser, were real people. Caroline, a wealthy New Yorker who championed causes related to the war, made the world a better place. Herta, a physician under Hitler, cast long shadows and destroyed people. The third, Kasia, was brutalized by Herta. Eventually she triumphs, thanks in no small measure to Caroline’s help.

The stories are told in the first person, from three points of view—Caroline’s, Kasia’s, and Herta’s. All are compelling, but the two that mean most are Caroline’s and Kasia’s. The women are foils for each other—and then again, similar. They’re both overcomers. They have their own ideas, and they stand strong in their beliefs, even as they demonstrate vulnerability. They come alive on the page and in the theatre of the reader’s mind. They’re believable. How their worlds intersect is at once moving; memorable. The horrors Kasia endures are partially redeemed by Caroline’s favor. She’s a conduit of grace and love, of healing and hope.

Kasia’s final confrontation with Herta gratifies the reader. It’s difficult to understand how Herta justified her war crimes. She’s a symbol of the Nazi mindset—so difficult to grasp for those of us born well after the war.

Before reading this book, I didn’t know Ravensbrück existed. I didn’t learn about it in K-12. It wasn’t part of any college history course. Even in my research as a journalist, it never surfaced. As The Guardian piece says, post-war coverage of the camp was minimal, at best.

Thanks to authors like Kelly, who took time to understand, interview, and reflect on the people and the era she wrote about, post-WWII readers can begin to seize the deeper meaning behind it all.

Leave a Reply