On Sept. 11, 2001, I was a Washingtonian, living near the Pentagon and working as an education reporter. As I darted to the subway, the sky glowed a crystalline blue. Later, everyone from D.C. to New York exchanged stories about the otherworldly brightness of that morning. How could a perfect day devolve into the darkest time in U.S. history? It became illustrative of 9/11 as a day of humanity’s starkest contrasts: our capacity for the deepest depravity; our capacity for the greatest good.

During my ninety-minute commute, I sifted through The New York Times and listened to the morning news on my Walkman’s trusty TV setting. Peter Jennings, efficient and calm as ever, reported on twin attacks at the World Trade Center. Jennings anchored the evening news; it was unusual for him to be at his desk that morning. His presence underscored the magnitude of the event.

Jennings—or someone on air with him—suggested Washington could be hit next. I called my dad in Ohio and asked him to turn on his TV. I needed visual affirmation of what I’d heard. If Washington was attacked, would I be safer at work, or at home? My dad encouraged me to keep heading to work, where I’d be surrounded by people.

As I walked into my office, I heard news of the Pentagon being hit. I fumbled, and my coffee thermos slid from my hands. As I chased it down the sidewalk, I thought: I live ten minutes from the Pentagon.

My colleagues crowded in silence around a black-and-white TV. We watched the towers fall. Our anxiety mounted as news reports said the fourth plane was headed for Washington, likely the Capitol or the White House. A few of us dialed our families, but the phone lines were dead.

We could do little more than stare at the TV, caught in a swirl of confusion and disbelief. By early afternoon, I grabbed a ride home with a coworker. The subway suddenly felt unsafe.

That night, my roommate and I walked across the Potomac to Georgetown. The streets were lined with armed guards. Tanks were wedged into alleyways. The skies, usually echoing with the noise of planes from National Airport, were eerily soundless. Our capital had become a military state.

A few days later, we drove to Pentagon City, a mall with views of the Pentagon, and gazed at the battered fortress. Coming face-to-face with evil’s path was far more jarring than the TV images of it.

Sept. 11 was a kaleidoscope of toxic sights and alarming sounds, images and sensations impossible to forget. It was the origin of the endless news scroll, an unlikely comfort in a surreal time. The steady influx of information was a relief, an anchor in a world gone apocalyptic.

Everyone alive that day, whether in New York and Washington, on the fringes, or far away, was stunned. We all have stories: tales of grief, loss, or redemption. Memories of man at his best, and at his worst.

Rebuilding

After 9/11, I went to Manhattan to cover the story of a college across from Ground Zero. It had lost students, and one of its major buildings sustained severe damage. In the weeks that followed, I covered every aspect of 9/11’s impact on higher education. Urgent, challenging, compelling—it was an assignment I’ll not forget.

When I landed my job, I didn’t imagine it might send me to a war zone within my own country. But it did, and I am grateful. Talking with people in New York who’d been directly affected by the attacks, telling their stories—these were invaluable lessons in empathy, in the resilience of the American spirit.

May we always remember Sept. 11. May we share with the rising generations what we learned from it, and what we continue to learn in its aftermath. As we do, we honor those lost at the World Trade Center and at the Pentagon. By remembering and honoring them, we offer a redemptive edge to the horrors of that day.

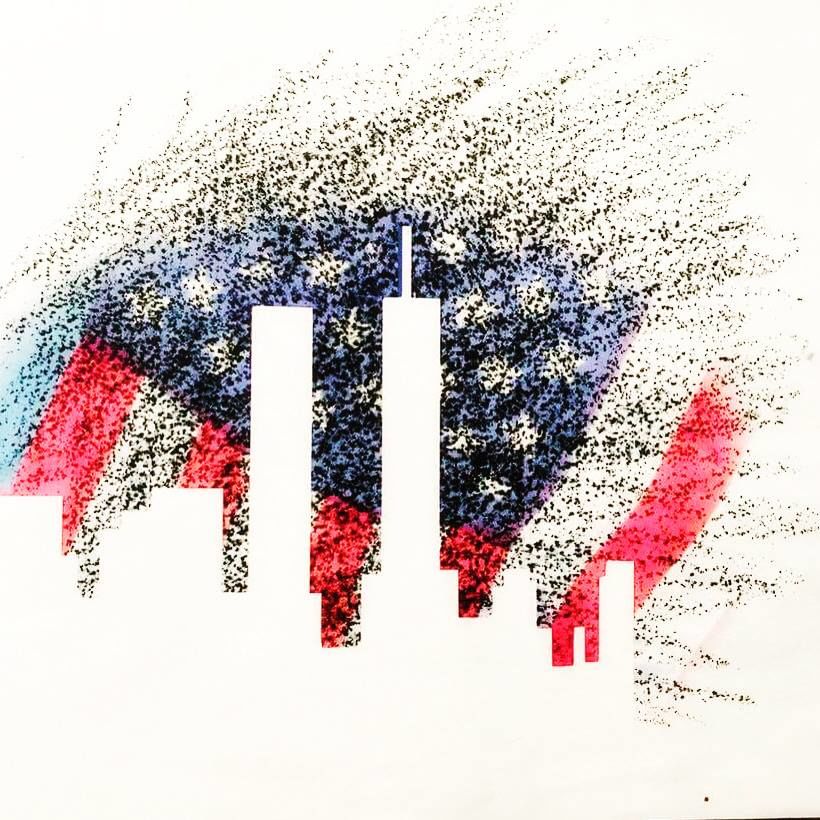

9-11-01: My colleague and friend, Mahendra Singh, created this illustration for the publication we both worked for at the time, Community College Week. It ran in our first post-9/11 issue.

Leave a Reply